Despite the scientific and

technological advancements of the modern world, we humans are limited by

cognitive and other psychological shortcomings that inhibit the capacity to

obtain objective truth. One that many are familiar with is confirmation bias,

which is the tendency to seek out and/or interpret information in a way that

supports pre-conceived ideas. Another is group think: humans have a deep need

to belong and to feel loved and accepted, and this often creates pressure to

conform to others in terms of dress, behaviour, and belief. Finally, there is

the basic fact that social and political reality is much too complex for our

brains to fully grasp, and hence we create “shortcuts”, or filters, that make

perception and information processing more manageable. One shortcut is

ideology, which is a tool to simplify reality in a way that diagnoses a problem

and that creates the motivation for political action. Another example is the

use of stereotype. We categorize both people and objects into generalized ideas

that help to simplify and prevent cognitive overload, and that contain often

misleading assumptions that influence interpretation. This is particularly the

case with the way we understand foreigners. When we meet someone who is not

from our own national group, most of us will almost immediately place them into

some national category that contains stereotypical assumptions (e.g., Canadians

are polite, Italians are mobsters, etc.). It also frequently happens with

gender; when meeting someone of the opposite sex we often make assumptions

about them (women are like this, men are like that). This tendency to

stereotype and simplify even when a more nuanced approach would be better is so

widespread that one might even assert that it is part of brain’s (faulty) cognitive

equipment.

So why, then, do many of us believe that we possess

objective political truth in the cosmic sense? And why, as a corollary, do we

tend to feel so confident of our beliefs and simultaneously think that

political opponents who think differently are either selfish, dumb, or morally

bankrupt? Jonothan Haidt’s Our Righteous

Minds goes some way in answering those questions. In this highly informed

and well written book, he shows the evolutionary basis of our politics.

Evolution has equipped humans with the mental tools to adapt to a range of

challenges. The formation of groups, and the difficulties and opportunities

that inhere to being a member of a group, are particularly important in this

regard. At the most basic level, groups have an adaptive challenge over

solitary individuals, and this was especially true in the harsh conditions in

which our primitive ancestors evolved. But in order for a group to enhance the

reproductive success of its members, it had to function properly. This means, inter

alia, that mechanisms for cooperation had to emerge, for they are necessary for

everything from rearing the young, to obtaining food, to coordinating war

efforts against other groups. It is this functional need for cooperation, Haidt

shows, which led to the development of our emotional brains. The basic emotions

that all experience, like fear, anger, love, desire, affection, disgust, and

joy arose in our evolutionary past because they furthered the reproductive

success of those groups that possessed them.

As humans organized themselves into larger and more

complex social aggregations, they developed more sophisticated forms of culture

and cognition which filtered our emotional universe. Humans not only developed

concepts to name the emotions they felt, but also rules that influenced how

emotions could be legitimately expressed. But in the long span of evolution,

this phase of culture and cognition is just a blink of an eye. For hundreds of

thousands of years, humans lived in contexts where the immediate and automatic

sensation of emotions was necessary for survival. The emotion of disgust, for

example, evolved to steer humans away from rotting or infectious matter, and

for it to fulfill its function it has to be felt immediately. Ditto for fear:

in the savannah, the hunter whose sensation of fear was automatic at the sight

of a predator would have certainly had an advantage over one who thought first

and felt later.

This evolutionary account of emotions provides clues

to the question of why people generally experience emotions in an automatic and

immediate fashion. Anger, fear, love, and other primal emotions are rarely the

result of interpretation or detached reflection. Rather, we feel these emotions

first and then interpret the event or

stimuli on the basis of these emotions. Both cognition and emotion are

information processing mechanisms, but the latter is much faster than the

former because we are physiologically built that way. And emotions’ precedence

in time translates to its predominance in interpretation and in influencing

human behaviour. This will not come as a surprise to anyone who has read the

findings of neuroscience, nor to those who, like me, come from cultures and

families that are unashamedly emotional through and through.

Haidt does not stop there. In Our Righteous Minds he also shows that our emotional dispositions

provide the basis for morality. Evidence shows, for example, that people who

have damaged the emotional parts of their brains are unable to make moral

decisions in a functional way, highlighting the dense nexus between these parts of the brain. Haidt proposes a list of moral senses that appeal to, or

trigger, primordial emotion: 1) care/harm, which was selected in response to

the challenge of caring for children, 2) fairness/cheating, which evolved to

improve cooperation and prevent exploitation, 3) loyalty/betrayal evolved to

help form coalitions, 4) authority/subversion was necessary to help identify

status hierarchy, and 5) sanctity/degradation provided the emotional basis of

religious rituals. These

traits exist in all groups, and although the diversity of their expression is

immense, the emotions that they appeal to are evolutionary selected adaptations

and hence universal to the human species.

The differences between small groups and larger ones

are particularly stark. Smaller groups, especially hunting and gathering

tribes, are more homogenous and hence the cultural expressions of emotions that

are foundational for things such as religious rituals and rearing the young are

more monolithic. As societies become more advanced, different moral matrices

emerge, and herein lies the emotional basis of political ideology: the Left,

according to Haidt, appeals the moral sense of care/harm and fairness/cheating,

while the Right appeals to all five.

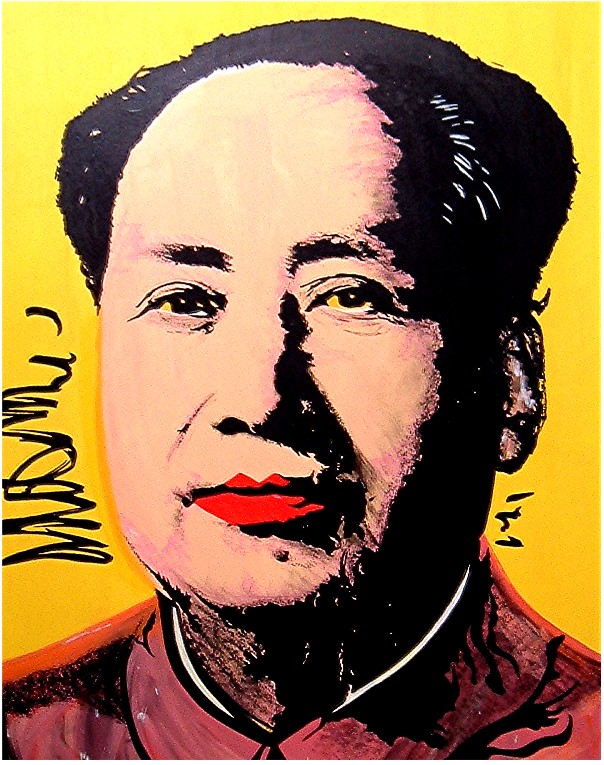

However, despite these differences between the Left

and the Right, at the civilizational level there remain shared basic assumptions.

The West is particularly relevant in this regard: Haidt shows that the

philosophical liberal assumptions that most Westerners, consciously or not,

presume—that persons are unique, autonomous, rational, responsible individuals

who should be free to choose their own destinies provided that they do not harm

others—are historically and civilizationally, in Haidt’s colourful acronym,

WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, Democratic). As most

anthropologists and those who have travelled to non-Western countries know, other

civilizations display more collectivist moral universes, which means that they

conceive of persons as moored or tethered into an organic whole that emphasizes

responsibilities rather than rights. This collectivist ontology is actually

more consistent with our evolutionary heritage, according to Haidt, because our

emotions are evolutionary adaptations selected

at the group and not the individual level.

Within the scholarly discipline of evolutionary

biology there has been a disagreement on whether our physical and mental traits

evolved in individuals or at the group level. To some the debate has largely

been settled; prominent members of the field, like Richard Dawkins and E.O. Wilson,

for example, do not accept the idea of group-level selection. As alluded to

above Jonathan Haidt disagrees and argues that our emotional brains could not

have evolved at the individual level because their very function is to enhance

the survival of the group by creating binding moral rules. Morality is intrinsically

relational and group based, and hence if our emotions are the basis of

morality, it suggests that our emotive traits are shared because they were

selected at the level of the group.

I am not an expert in the field but I find Jonathan

Haidt’s arguments to be more convincing. The need to belong, and to be loved

and accepted seems to be such a deep and primordial attribute of all human

groups. The Western conception of rational and autonomous individuals with

natural rights reflects intellectual and cultural developments that are

historically unique: medieval Church lawyers first conceived of the idea of

natural rights based on their religious worldview of the importance of individual salvation (this contrasts

with other religious worldviews which emphasized the need to create a more just

political and social order). The scientific revolution that began in the 15th

and 16th centuries, the invention of the printing press, the

Protestant Reformation, the rise of secularism, the French and American revolutions,

all contributed to the long term process whereby the religious idea of natural

rights became the secular version of human rights that most Westerners (and

many non-Westerners) take for granted as a natural part of the moral universe.

These developments, in a sense, have taken us farther and farther away from the

collectivist moral matrices that our brains are still equipped with, at least at the physiological level.

I would even hypothesize that these developments

help to explain some of the pathologies that are endemic to rich and

Westernized societies: depression, anxiety, ennui, and anomie. The founder of

sociology, Emile Durkheim, made this observation long ago. He wanted to

understand why suicide was more prevalent in the rich Protestant countries compared

to poorer Catholic societies, and he observed that the former’s more radical

individualism led to a sense of alienation and a belief that failure was purely

the responsibility of the individual person while poorer Catholics were still

tethered to collective moral and social contexts which helped them to cope with

their difficulties and shortcomings. The implication is that the distancing

from the more group- orientated moral matrix that was ushered in by the

Protestant Reformation also helped to weaken the sense of belonging and group

feeling that were part of the human species natural habitat for millennia. I

think Durkheim’s framework can explain many other phenomenon, not only suicide.

For example, why do many young, educated Westerners go and fight and die for

ISIS even though in their host societies they enjoyed all the goodies that

Western standards of living provided? One reason might be a deep dissatisfaction

with the materialist and individualist ethos that suffuse most Western societies.

Many people feel this and deal with it in healthy ways, such as joining

political and religious/spiritual groups or devotion to family and community,

while others use alcohol, drugs, sex, or anti-depressants to numb their pain.

For some, joining a religious militant group that is fighting to establish a collectivist

Islamic utopia also fulfills this function. It is no coincidence that Islamists,

in their recruitment propaganda, routinely denounce the secularism, liberalism,

and materialism of the West. They are appealing to the frustrations of many, especially

disaffected young men or those who reject to Western modes of living.

Although Jonathan Haidt is a left wing American

liberal, his book subtly challenges liberals and libertarians who favour a

political and social order organized around the metaphysical assumptions of

rational, autonomous, and responsible individuals. His data suggests that the

development of a liberal civilization is quite the achievement in light of the

fact that physiologically our brains evolved emotional mechanisms that are more

consonant with group-orientated moral matrices—an observation borne out by the

fact that pretty much all non-Western

civilizations are more collectivist, in terms of their conception of the

universe and humans’ place within it. Thus the purported universality of

Western political forms—like individual rights and democracy—are not universal

at all and are rather historically and culturally contingent. This should give

an attitude of humility when faced with others who think differently,

especially for the liberal interventionists who often triumphantly proselytize

their creed in international affairs.

Haidt’s book also councils humility about what we

can truly know about the social and political realm. Our political and

ideological frameworks are, at bottom, different emotional reactions to the

organization of society, and these emotions are the product of an evolutionary

history that is radically different from the contemporary era. Our primitive

ancestors lived in conditions that necessitated emotions that were automatic

and immediate and that influenced their interpretations of environments, not in

the sense of providing objective truth but in terms of enhancing survival.

Hunters had to feel certainty that the predator in the distance would kill them

in order for them to flee, and this is true even if their perception was wrong.

Hundreds of thousands of years later, we humans still interpret reality with

certainty because, simply, our brains are designed that way. Applied to other

social issues, this certainty translates into a self-righteous attitude that

contributes to the tribalism of political life: the sense that we are right,

the other is wrong (or dumb, or selfish, etc), and that’s that. This atavistic impulse

towards tribalism has ironically been accentuated by the rise of digital media,

suggesting that the techno-utopian vision of internet as some liberating and

cosmopolitan force is premature.

Of course, Haidt’s argument that we are driven by

emotion is not original. The ancient Roman poet Ovid said that “desire

and reason are pulling in different directions. I see the right way and approve

it, but I follow the wrong”. David Hume famously said that humans are “slaves

to their passions”, an observation which contrasted with the veneration of

reason professed by most of his contemporaries (especially in France). Haidt’s

book shows, using plenty of data collected with modern scientific methods, that

the insights of Ovid and Hume were right.