Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice tells the tale of Gustov Von Aschenbach, a middle-aged and successful German novelist during the early 20th century. Aschenbach’s works are widely read, among general audiences but also in schools as pedagogical tools to teach the techniques and methods invented by masters of the art. As a consequence, Aschenbach has a successful career with a materially comfortable, even affluent, existence, with multiple homes, each for a different season, and servants to attend to his needs. And yet he experiences what today many would call a mid-life crisis. In his early 50’s, already widowed, and deeply unsatisfied with the elements which weave the fabric of his life—the routines, surroundings, frequent contacts, work and leisure habits. While out for a stroll in this gloomy state, he spots a foreign looking man who evokes the idea that he needed a foreign adventure to free him from his emotional and spiritual cul-de-sac. Exotic food and a hotter climate, a beach from which one can soak up the sun and bathe in the warm waters of the Mediterranean—these, thought Aschenbach not unreasonably, would help lift his spirits and bring back his zest for life.

The rest of the plot revolves around this adventure. He takes the train to the coast, and from there, goes to Italy via passenger ship. Perhaps representing an omen of his coming misfortunes, on the ship the food was horrible, the quarters uncomfortable, and among the passengers there is a group of performers composed mostly of young men, but among this group is an inebriated old man who tries to hide his age using various articles—his hat, glasses, hair, etc. His attempt to fit in, as it were, could not efface the sagging skin, wrinkled hands, brown or missing teeth, and other signs of the passage of time, of decay and decline, which, as we will see, is a major theme in Death in Venice.

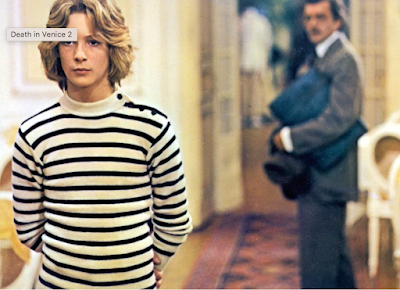

There are two key events in Venice which seal Aschenbach’s fate. The first, and most important, is the presence of another guest, a statuesque and gorgeous Polish boy of 14 years old named Tadzio, a member of the aristocracy, who is vacationing with his family. Aschenbach almost immediately becomes infatuated with him. This fateful—and ultimately fatal—attraction was almost nipped in the bud because, shortly after arriving, Aschenbach decides to leave Venice as he found the stifling summer heat intolerable. When he arrives at the train station, he discovers that the hotel mistakenly sent his luggage to another destination, and so as fate would have it, Aschenbach remains in Venice.

|

| A Fatal Attraction |

While there, his obsession for Tadzio only deepens, perhaps because it is never consummated, nor is the attention equally reciprocated. Aschenbach sees Tadzio frequently in the hotel restaurant and on the beach, and in the latter location, he could focus on the perfectly picturesque proportions of Tadzio’s exposed youthful body. There are a few fleeting moments when it appears as if Tadzio notices he is being watched and reciprocates the attention, and, of course, the infatuated Aschenbach imagines that perhaps the boy feels the same way. But the skeptical reader could just as easily conclude that Tadzio was motivated by mere curiosity, and that even if he were gay, attraction to the aging Aschenbach was perhaps not the motive for the momentary glance.

In one scene, Aschenbach sees Tadzio up close and notices that there are signs of sickliness—he has fragile not gleaming teeth, and anemic skin. Below the surface of Tadzio’s godlike beauty, therefore, was a very different and ominous reality.

The city of Venice has a similar dynamic. In some of the more beautiful passages of the text, the reader encounters vivid descriptions of this unique city’s splendors and wonders—its zigzagging canals pass by medieval buildings with Greco-Roman columns, Arabesque windows, and Byzantine cupolas. This beautiful landscape is enriched by the tourists from all over the world filling the streets and alleys, adding colour to the local population of hot blooded and passionately expressive Italians. But the reader soon discovers that there is a Cholera outbreak in Venice, and that the corrupt authorities were reluctant to reveal the truth about it because it would devastate the tourist industry. Aschenbach suspects something is awry, particularly when he notices public health officials disinfecting public spaces, and the streets slowly emptying, but locals respond to his inquiries with lies, saying it’s a routine measure. Finally, he discovers the truth from—perhaps not surprisingly—an Englishmen who works as a customs official in the city. The disease, which spreads through water and leads to an excruciating death among a staggering 80% of the infected, arrived via boat, and officials’ attempts to stop the epidemic were an utter failure. Aschenbach himself contracts the disease and eventually dies while sitting on the beach staring at the object of his obsession.

This ignominious outcome, of course, could have been avoided had Aschenbach left Venice earlier, as he had wanted to. The reason for staying, as mentioned above, was that his luggage was mishandled, but the text makes clear that this was not determinative. Aschenbach nudged fate in his preferred direction, or did not resist fate when it accorded with his wishes. For example, one reason for his luggage being mishandled was that he wanted to stay in the hotel just a bit longer to capture a few more glimpses of the beautiful boy, even though there was a car ready to take him and his luggage to the train station where the train would soon be departing; at this moment, he instructs the hotel staff to send his luggage to the station, while he would arrive shortly after. When he finally arrives, he discovers that his luggage was mishandled, but he still could have boarded, and waited for his luggage at the next destination. Instead, with the boy at the forefront of his mind, he chooses to stay in Venice with the excuse, or rationalization, of his missing luggage. When the fateful decision to not board is made, his sense of relief is palpable, because now it would mean he could continue to indulge his puerile fantasies in Tadzio’s presence.

A connecting theme in the subtext is decay or rot beneath the visible or superficial beauty. This is not surprising, given that another classic by Thomas Mann read by my book club, Buddenbrooks, has similar themes (my review of that book can be found here). Below the surface of Aschenbach’s affluent life, and successful career, one discovers depression and deep dissatisfaction; under Venice’s strikingly beautiful fairytale like façade, there is a raging epidemic which kills by, among other things, starving the body of necessary fluids, and a corrupt administration unwilling to be honest about it; and, of course, the godlike and statuesque beauty of Tadzio only temporarily hides the underlying anemic disposition which was a manifestation of poor health and, at least at the time, predicted an early grave. The major truth that Thomas Mann seemingly wants to impart—in my view successfully—is to look below the surfaces, as appearances are deceiving and misleading; a little probing almost always reveals a darker, menacing, reality which afflicts all living things, whether they are humans, cities, or societies—decay, rot, disease, fragility, and death.

This review would not be complete without a few lines on the aesthetic quality of Death in Venice. On this point, all the members present at the book club meeting agreed that the text is beautifully written, much more than, say, is the case with Buddenbrooks. Not only is the prose poetic while rendering the scenery visually stimulating; there are many lines which provoke deep thought. For example, while sitting on the beach, Aschenbach reflected on his love the sea as it satisfied:

“the desire to take shelter from the demanding diversity of phenomena in the bosom of boundless simplicity, [and conveyed] a propensity for the unarticulated, the immoderate, the eternal, for nothingness. To repose in perfection is the desire of all those who strive for excellence, and is not nothingness a form of perfection?”

This line stuck out for me and for other members of the book club, as it is emblematic of the prose as it appears throughout the text—flowery, poetic, philosophical, but also very beautiful. It was partly for this reason that all members rated Death in Venice very highly. Sadly, it will be my last book club meeting for a while, as I will soon be going overseas to start a new teaching position, and may not be back in Toronto until the Spring or Summer of 2023. In the meantime, of course, I will continue to read the classics and post my reflections on this blog.