|

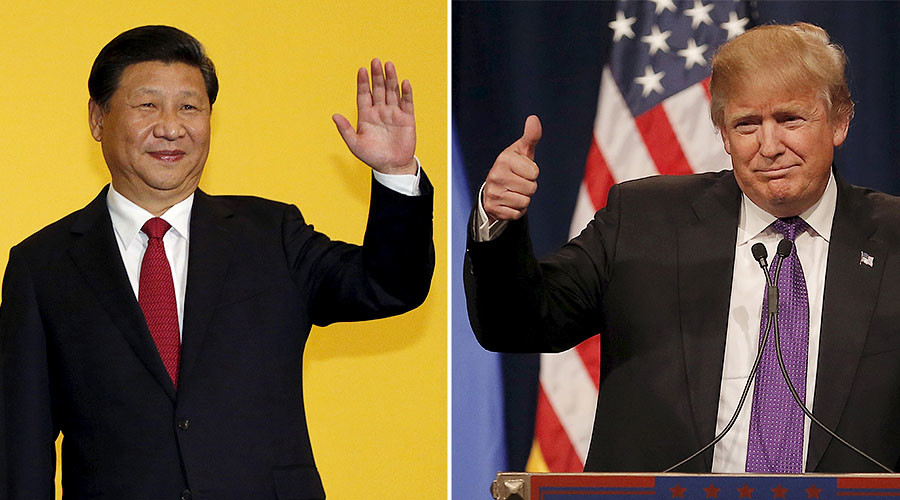

| The main contenders |

Another aspect

of power transitions is a “closing of space”: the established and rising powers

repeatedly “bump” into each other, leading to minor skirmishes. Alliance

formations are a major reason for these disputes, as a distinguishing feature

of the established power is defense and economic ties to countries that feel

threatened by the rising one (sometimes called “encirclement”). These ties help

balance the rising power, but only up to a point. When allies begin to feel

that the hegemon’s commitments to their security are not secure, they either

beef up their own defense capabilities, consider developing new security

arrangements or defect to the rising power.

Lastly, Gilpin

shows that the society of the declining power is characterized with an

increased rights-based mentality that emphasizes individual (and hence

domestic) needs and wants over international ones. There are also major

domestic disputes about which rights should be satisfied, leading to fierce

political conflict that becomes difficult to bridge. As polarization increases,

a blame game ensues as each side of the political divide blames the other for

the general decline in economic well-being. Conversely, in the rising state a

sense of duty to contribute to the nation’s destiny prevails. There is a

relatively accepted consensus that it will soon assume leadership of the

international system and that citizens, in both public and private sectors,

should contribute to the attainment of that goal. Confidence is high in this

society because it is growing fast and rapidly increasing investments in the

military, while the established power is divided, insular and increasingly

prioritizing domestic needs over international ones.

This picture

more or less characterizes the relationship between the US and China over the

last fifteen years, and Trump’s victory needs to be placed in that context. Not

coincidently, his rise coincides with some significant inflection points:

China’s economy is now roughly equal in size to America’s, it is the world’s

largest manufacturer, and its military expenditure is growing at double-digit

rates. Current trends suggest that China will soon overtake America as the

world’s leading state, and Americans are fiercely divided about how to manage

the domestic and international challenges posed by this power transition.

Thus it is no

coincidence that Trump’s major target is China or that his main campaign

slogan, “Make America Great Again” is an implicit recognition of a sense of

American decline. Other patterns fit the mold; as Gilpin might have predicted,

China and the US are increasingly “bumping into each other”, as China makes

territorial claims against America’s allies in the region. The domestic and

psychological changes identified by Gilpin can also be observed. While the US

is polarized, pessimistic, and prioritizing domestic needs, China is

increasingly confident and becoming bolder in challenging the US-led order.

Philippino President Rodrigo Duterte’s surprising defection to China despite

his country’s long alliance with the US may be a sign of more to come.

Gilpin’s

analysis of power transitions over 2500 years show that more often than not they

result in war. In all the international power transitions he analyzes

(Peloponnesian War, Punic wars, the Crusades, 30 years’ war, Napoleonic wars,

World War 1), war was preceded by structural shifts in the distribution of

power, an unwillingness of the established power to accept decline, the rising

power’s increasing assertiveness and claim to rightful leadership, leading to

disequilibrium, tensions, skirmishes, and conflict. This does not bode well for

the Trump administration. Soon enough Trump may face a crisis in South

East Asia that will test his resolve to defend a status quo characterized by waning

American leadership. The alternative is to accept the structural shifts taking

place and accede to China’s effective control of the region. If he refuses to

bow to China’s claim of regional leadership, a high-stakes war is very likely. Gilpin

shows that, during these types of “hegemonic” wars, at stake is not only or

mainly military dominance, but also whose societal model gains prestige,

radiates outwards and becomes the norm. A victory for China in any standoff

with the US would also mean a triumph of China’s model of authoritarian

state-capitalism, giving liberal democracy another major blow.